Biography

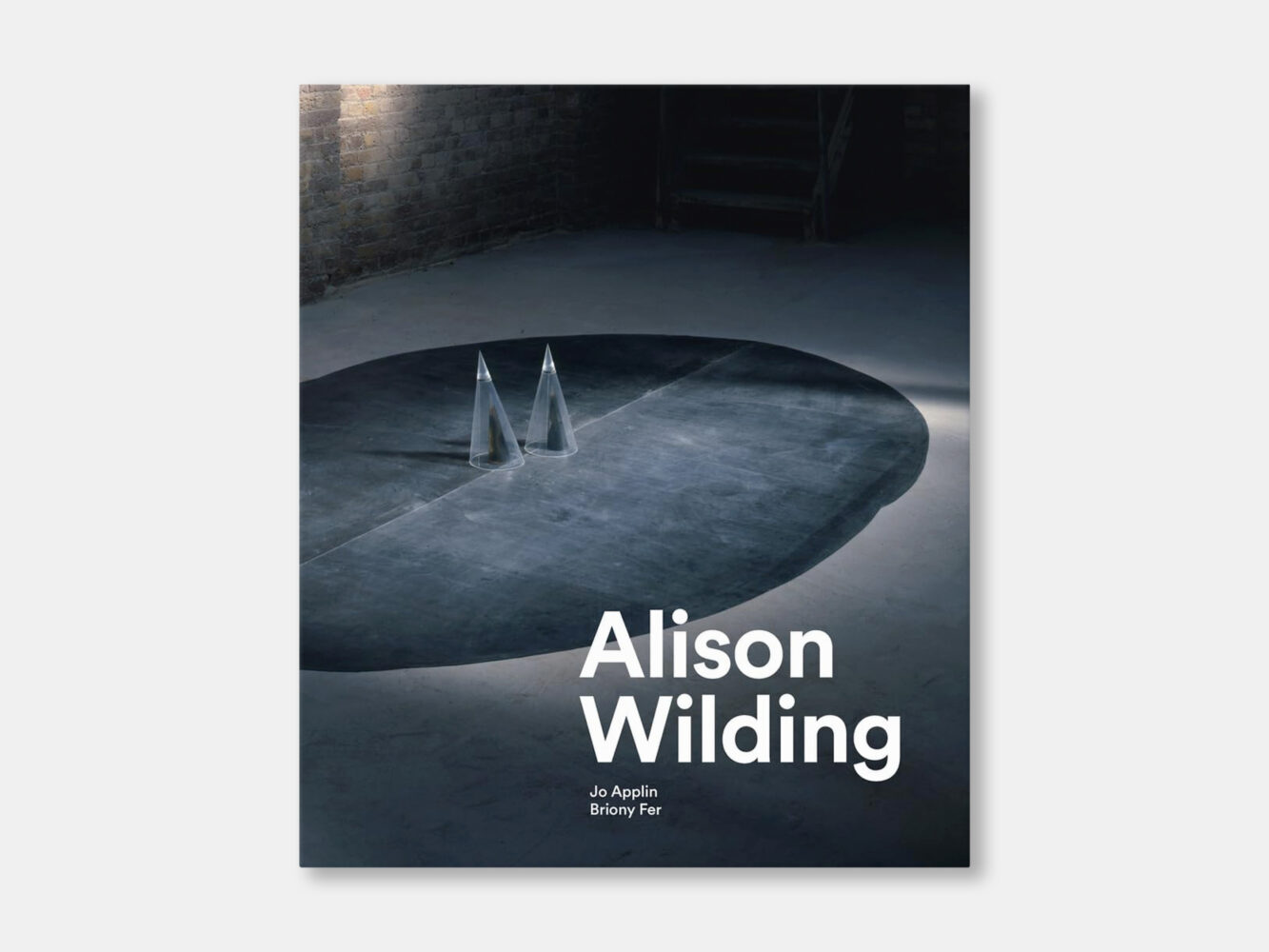

‘I’m not obsessed with materials’, says Alison Wilding OBE RA (b.1948, Blackburn, UK). ‘If I’ve used a huge variety of stuff over the years, it’s because there’s lots of it freely available in the world. I don’t believe in a hierarchy of materials. All materials, however mundane, can be transformed’.1 Wilding is one of the most important British sculptors of the post war period. Her (mostly) abstract sculptures, as the artist describes, cross both scale and materials, often in single works that push together unexpected and emotive relationships. From small tabletop or wall mounted works, to giant, room filling installations, made from alabaster, wood, steel, rubber, paper, copper and sand, Wilding’s recurring interests in balance, weight, line, material, and concealment are continually evident in a body of work that has constantly evolved since she first began exhibiting in the 1970s.

Wilding studied at Nottingham College of Art in 1966, at Ravensbourne College of Art and Design from 1967 to 1970, and then the Royal College of Art from 1970 to 1973 (where she was the only woman in her year group). Rising to prominence in the 1980s as part of the so-called New British Sculpture, Wilding has since been twice nominated for the Turner Prize (1988 and 1992) and was made a Royal Academician in 1999. Karsten Schubert London began representation of Wilding in 1987. She has exhibited internationally with solo shows at MoMA, New York (1987), the Serpentine Gallery, London (1985) and a retrospective at Tate Liverpool (1991). Her work is also on permanent display in the Tate Britain, London.

Wilding has constantly experimented with the boundaries of sculpture, side-stepping any traditional value orders, using the found and the made, the expensive and cheap with equal importance. ‘I like stuff and not particular materials’, the artist once explained. Wilding’s works sit on the floor, lean precariously against walls, stand proud and, at times, seem to shift in proportion and definition as the viewer moves around the work. The involvement of the viewer, who must kneel, peer inside, duck under or step over the pieces to experience a reveal, has been a central focus of the artist’s production since her early exhibitions of multi-part installations.

Alongside Wilding’s practice of sculpture making is a consistent interest in producing drawings. For Wilding, these works on paper possess a freedom that is impossible to replicate in sculpture, a practice without gravity in which ‘the right way up’ is always open for interpretation. These works on paper and the artist’s famous notebooks, in which works are numbered, thoughts are discussed, and ideas are sketched out, provide a fascinating and at times unexpected insight into this artist famed for her sculptural configurations.

After graduating from the Royal College of Art in the 1970s, Wilding began her career in London. Her early exhibitions reflect the popularity of conceptual art at the time, but even these works show that Wilding was, above all else, a sculptor of materials and shadow. An early work, Without Casting Light on the Subject (1975), is a photograph of a table and desk lamps with a printed text below. The text describes the objects shown, as well as the impossibility of one of the lamps illuminating the objects from its position. Move forward to Wilding’s Echo (1995), a large floor piece composed of strips of steel slotted together, partially concealing a brass ball hidden within the structure’s interior like a pearl in an oyster. In both these works, the artist’s interest in what can been seen, and what something appears to be, are a central motivation. Echo, whose title comes from myth of Echo and Narcissus from Ovid’s epic poem of vanity and adoration, reveals another aspect which reoccurs throughout Wilding’s work: stories and people. Wilding may be an abstract sculptor, but her practice is very much related to human desires and bodily encounters. As Wilding has expressed, ‘sculpture can be sexy’.

Wilding’s work of the mid-80s onwards becomes increasingly confident and unique to her own, ever more masterful visual language. Her works can be at once hard and playful, experimental yet grounded in an understanding of the language of sculpture, from Bernini to Brancusi to Sera. Alison Wilding continues to push forward her art, working in her East London studio daily and researching, looking and thinking about sculpture constantly. The evolution and ambition of the work continues to expand and evolve, as she propels her practice with an ever-broadening set of possibilities.

[1] A conversation between Alison Wilding and Sarah Whitfield, ‘Beauty/Speed/Devastation’, in Acanthus, Asymmetrically (London: Offer Waterman, 2017), n.p.

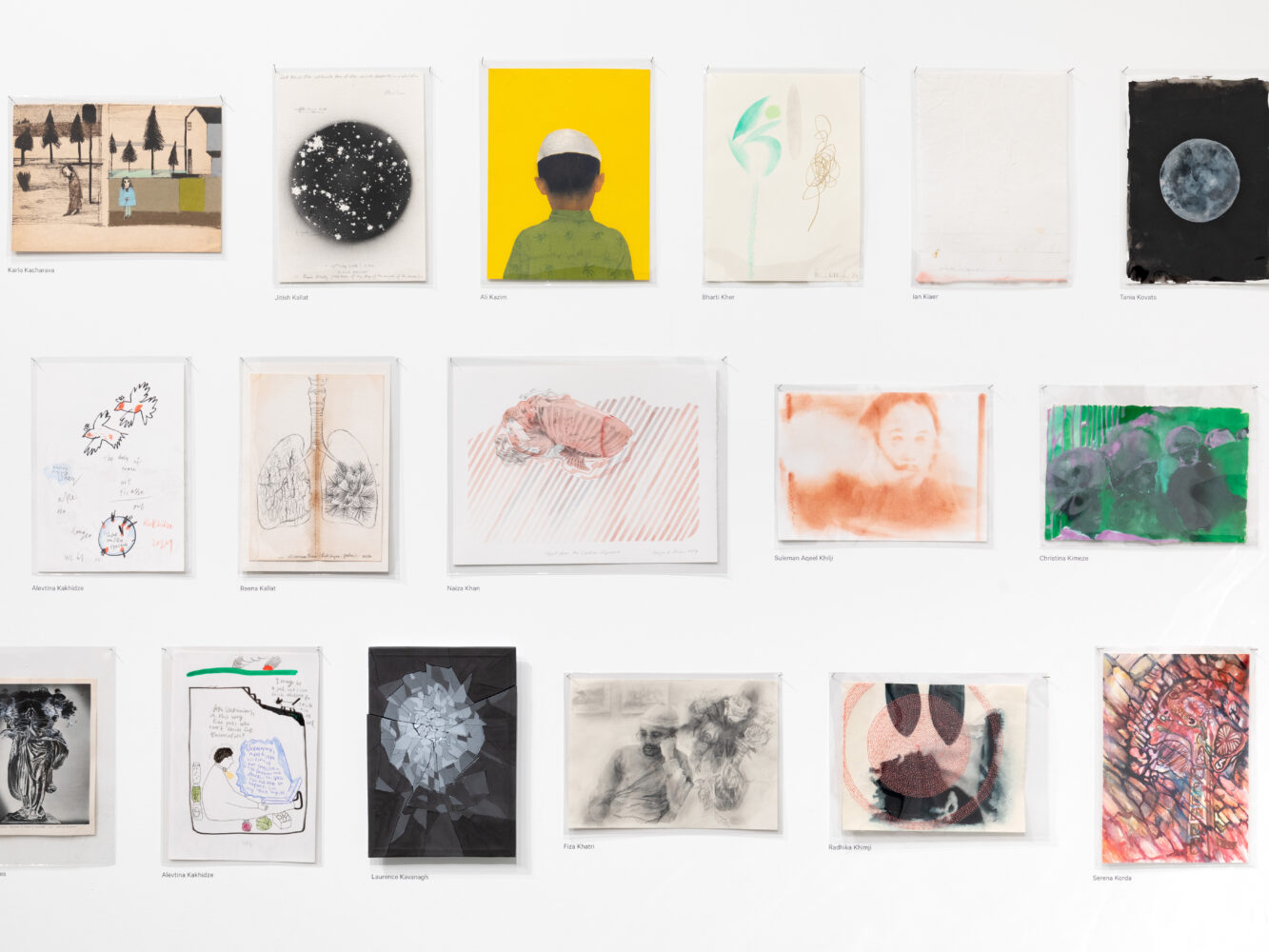

Works

Press

Sculptor Alison Wilding: ‘Some of my works are very huggable. But I don’t want anyone else to touch them’

September 2024

The Art Market: Alison Jacques has taken on representation of the sculptor Alison Wilding

March 2024

Exhibitions

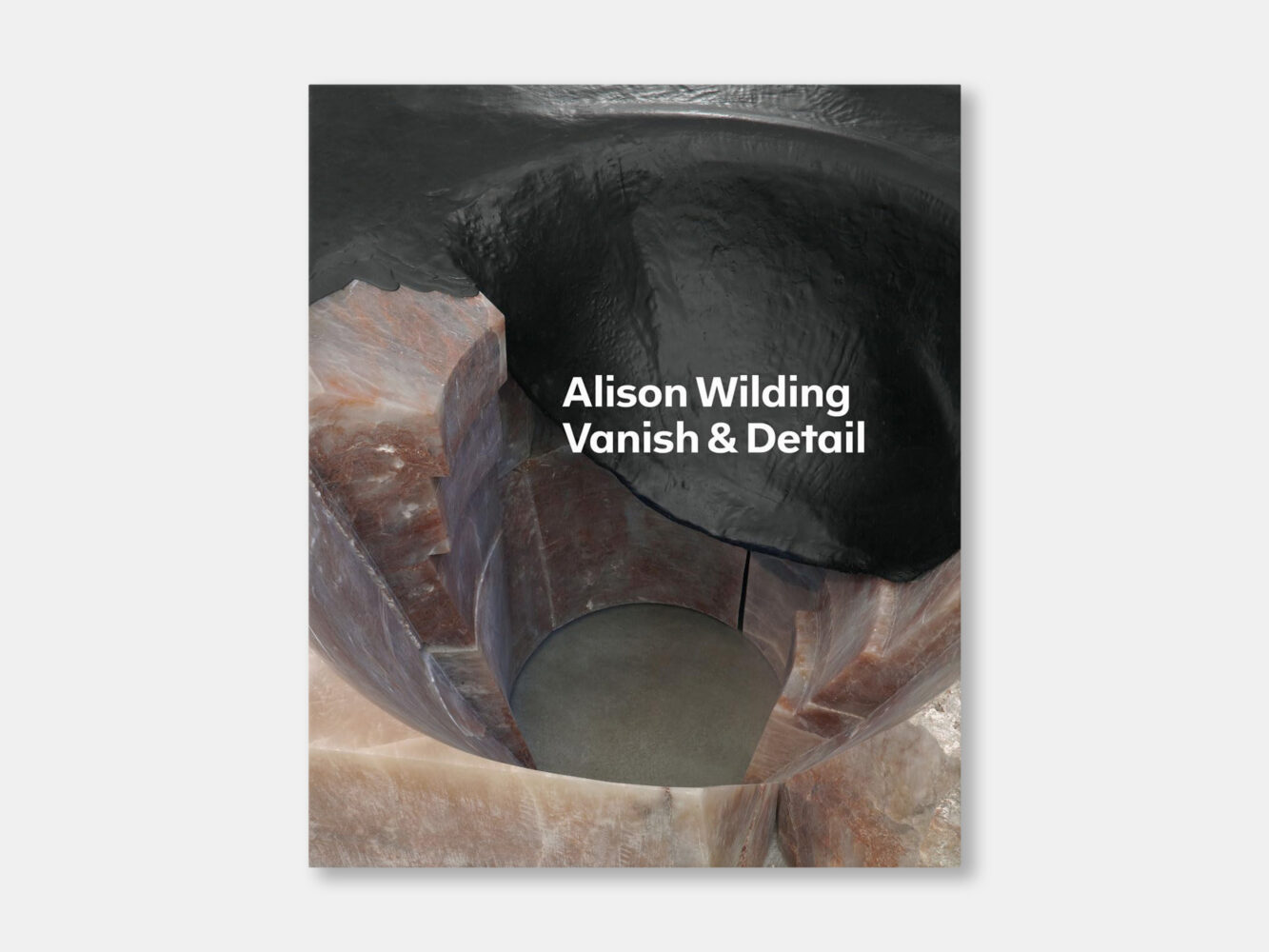

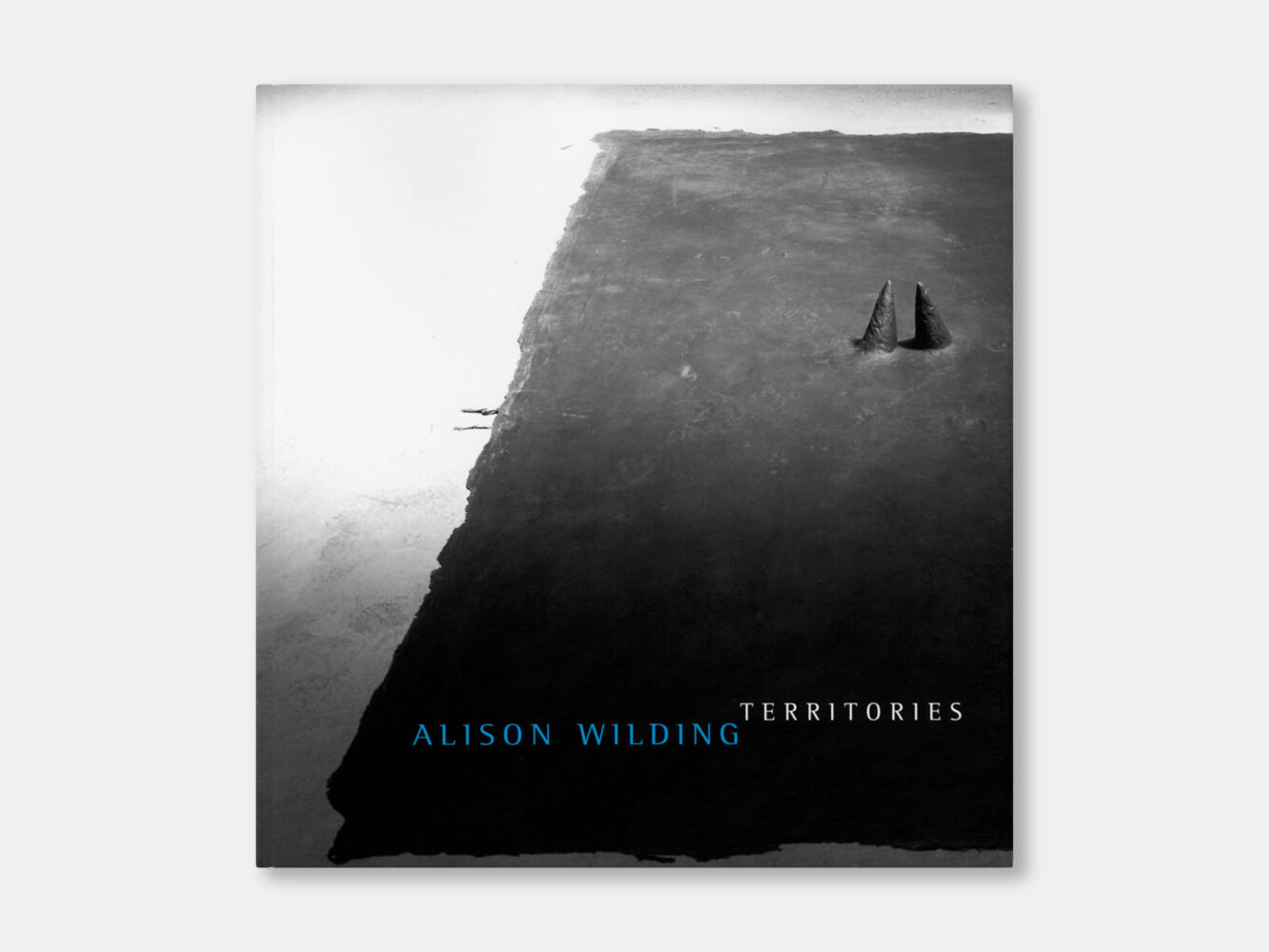

Books

News

Alison Wilding

in ‘Sublime Geometries: Selections from The William Louis-Dreyfus Foundation’, Katonah Museum of Art, New York

Alison Wilding

in ‘Piet Mondrian to Alison Wilding the Karsten Schubert bequest’, British Museum, London