Text

Alison Jacques is proud to present an online exhibition of works on paper by Betty Parsons. Spanning 25 years, from 1950 to 1975, these rarely shown paintings provide further evidence of Parsons’ vital contribution to the history of modern American art, as both a revolutionary gallerist and a pioneering artist in her own right.

At the age of 13, in 1913, Betty Parsons (née Betty Bierne Pierson) attended the Armory Show in New York, a landmark exhibition that, for many, provided an introduction to modern American art. ‘I knew then that I wanted to be an artist,’ Parsons said. ‘That I was an artist! It took a long time to get free. But, you see, I’ve always had this great energy and I believe in the expanding world.’1

Parsons was born, in 1900, into wealth and aristocracy; as a child, she travelled in cars emblazoned with the family crest. Following the Civil War, her grandfather, John Friederich Pierson, entered the family business, Ramapo Iron Works, and became a partner at Josiah G. Pierson and Brothers, amassing a fortune in the process. Parsons’ father, J. Fred Pierson, Jr., inherited John’s wealth but not his business acumen. ‘My father spent his life losing money’, Parsons later said, with acerbity. ‘He had a gift for that.’2

Following her experience at the Armory, Parsons begged her parents to enrol her in a women’s liberal arts college in Pennsylvania; instead, she was registered at the finishing school of Mrs Randall MacKeever. In response, Parsons initiated a charmingly adolescent form of protest, locking herself in her room, refusing food and speaking to no one. ‘When she emerged, Lee Hall recalls, ‘she wore trousers, she had slicked her hair to one side, she dangled a cigarette from her mouth’3. Her father conceded; Betty supplemented her education in the studio of Gutzon Borglum. (Borglum would go on to carve the presidential heads into Mount Rushmore.)

In 1919, Parsons married Schuyler Livingston Parsons; the newlyweds embarked on a nine-month European honeymoon in a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce. In the ensuing ten years, however, Parson was beset by ill fate. Having moved to Paris in 1922, enrolling at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière alongside Giacometti and Isamu Noguchi, Parsons divorced Schuyler and was subsequently disinherited by her family. In 1929, at which point she had settled in Montparnasse amongst such luminaries as Gertude Stein and Alice Toklas, the Stock Exchange crashed. The Parsons fortune disappeared. Parsons’ alimony stopped overnight.

In retrospect, this hardship paved the way for Parsons to become, as Ellsworth Kelly described, ‘an extraordinary woman in the history of modern art’.4 In the coming decade, Parsons gained vital experience in commercial galleries in New York, exhibiting her figurative paintings at an increasing rate across the US and Europe. In the mid-1940s, she was awakened to abstraction, a pivotal reorientation of focus inspired by a trip to the rodeo: ‘I saw all the movement, the noise, the color, the excitement, the passion. I thought, my God, how can you ever capture this except in an abstract sense?’5

For the remainder of her career, Parsons pursued – allowed herself to be led by – the soulful essence of abstraction. (She termed it ‘invisible presence’.) Having inaugurated the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1946, she curated ‘The Ideographic Picture’ in 1947, a show featuring the likes of Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still, thus initiating a pioneering programme of abstraction and establishing herself as one of the most visionary gallerists of recent history. As Helen Frankenthaler noted in 1992, ‘Betty and her gallery helped construct the center of the art world’.

But from the centre, she looked out, maintaining a devoted and energetic artistic practice for much of her life. With the potent restlessness known only to those who must create, Parsons produced a wide-eyed and joyous body of paintings and sculptures that rearticulated the world in abstract terms, not portraying the details of life but the imprints they left. Light was spoken through colour, movement through shape, life through space. As Parsons scribbled on the back of Untitled (1957), a gouache and pen work included in this online presentation: ‘The subject of art is the feeling of being alive now and the feeling of being alive at any time’. As she wrote in an early memo: ‘I’d rather paint than breathe.’6

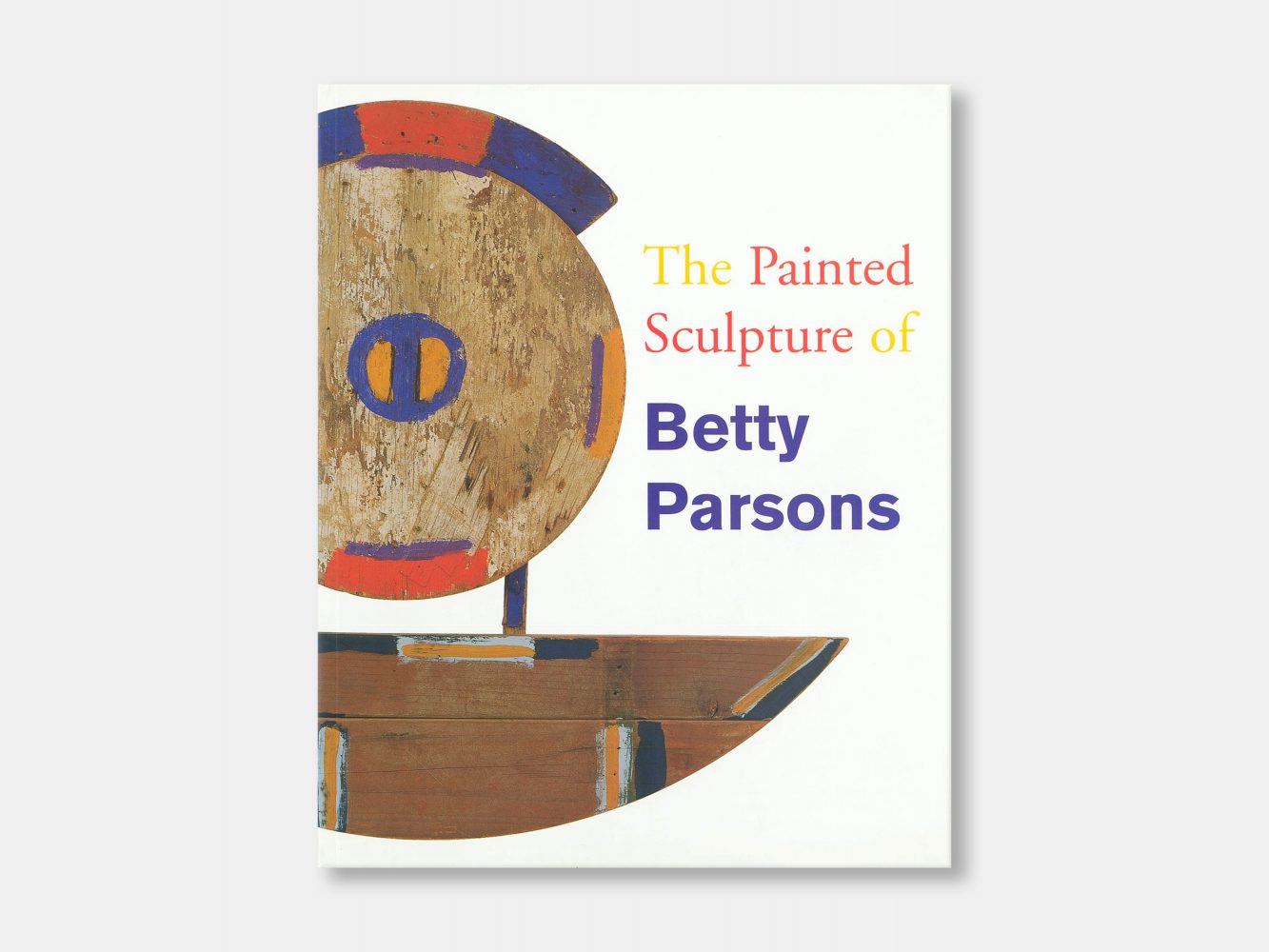

Just as Parsons’ sculptural works are constructed from flotsam gathered in Long Island, her works on paper represent a painterly uniting of scattered things. ‘The first time I met Betty’, recalled Lawrence Alloway ahead of Parsons’ 1968 exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery, London, ‘[she] gave me a clue as to the occasional nature of her art’. While the pair were driving across New York State in 1958, Parsons was dutifully painting in a sketchbook, a lifelong habit adopted from Arthur Lindsey in Paris. ‘A geometric zig-zag would be snatched out of a house we glimpsed’, Alloway notes, ‘smudges of brown were suggested by a hillside; blue tatters would record a moment’s weather; a white would be suggested by a duck in a pond.’

In such works on paper as Looking Out (1974) and Eyes and Garden II (1956), included here, we glimpse the duck, the house, the hillside. In the open expanses of Nova Scotia (1967–74) and Heading North (c.1975), we feel how it might feel to trade the muchness of the city for boundless country skies. As this curated presentation illustrates, Parsons’ works on paper are at once negotiations of colour, studies in non-literal representation, games played with and within bounded space. But they are also a sensory record of what it is to pass through the world: the way in which its many lines, colours and shapes blur into something that we call, interchangeably, abstraction or life itself.

‘Painting is not what you see’, reflected Parsons in a note from the early 1920s, ‘it’s a kind of energy light…a form of life…catching the spirit to keep it from speeding away.’7

- Lee Hall, Betty Parsons: Artist Dealer Collector (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1991), p.17

- Ibid., p.17

- Ibid., p.24

- Carol Strickland, ‘Betty Parsons’s 2 Lives: She Was Artist, Too’, The New York Times, 28 June 1992

- Ken Kelley, ‘Betty Parsons Taught America to Appreciate What It Once Called “Trash”’, People, February 1978

- Betty Parsons Gallery records and personal papers, c.1920–91, box 39, folder 5, Archives of American Art <www.aaa.si.edu/collections/betty-parsons-gallery-records-and-personal-papers-7211/subseries-7-2/box-39-folder-5>

- Ibid.

Works

-

![]() Untitled, c.1950

Untitled, c.1950 -

![]() Untitled, 1951

Untitled, 1951 -

![]() Untitled, 1953

Untitled, 1953 -

![]() Untitled, c. 1954

Untitled, c. 1954 -

![]() Maine, 1955

Maine, 1955 -

![]() Untitled, 1956

Untitled, 1956 -

![]() Eyes and Garden II, 1956

Eyes and Garden II, 1956 -

![]() Untitled, 1957

Untitled, 1957 -

![]() Untitled, c. 1960

Untitled, c. 1960 -

![]() Untitled, c. late 1960s

Untitled, c. late 1960s -

![]() Untitled, c. early 1970s

Untitled, c. early 1970s -

![]() Forms on a Brick Wall, 1972

Forms on a Brick Wall, 1972 -

![]() Untitled, c.1972

Untitled, c.1972 -

![]() Nova Scotia, 1967–74

Nova Scotia, 1967–74 -

![]() Looking Out, 1974

Looking Out, 1974 -

![]() Heading North, c.1975

Heading North, c.1975 -

![]() Under Sea, 1975

Under Sea, 1975