Biography

Robert Mapplethorpe (b.1946, New York, US; d.1989, Boston, US) was born in 1946 in Queens, New York. One of six children, he was brought up in a strict Catholic environment. (‘The way I arrange things is very Catholic’, he would later tell the BBC, ‘very symmetrical.’1) When he was 16, he enrolled at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where he first declared a major in advertising design before transferring to graphic arts. The change of direction allowed Mapplethorpe to explore his burgeoning interest in painting and drawing, and he would go on to produce a number of mixed media works that owed as much to Francis Bacon and Joseph Cornell as they did to the religious iconography of his upbringing. In 1970, at the Chelsea Hotel, the artist and filmmaker Sandy Daley gave him his first Polaroid camera. The initial intent was to incorporate his own photographs into his collages, but he quickly warmed to the camera’s expediency and the manner in which it could render light. Between 1970 and 1975, Mapplethorpe made over 1,500 photographs with Polaroid cameras, an early sign of his prolificacy. His first solo exhibition, in 1973 at Light Gallery in New York, was titled ‘Polaroids’.

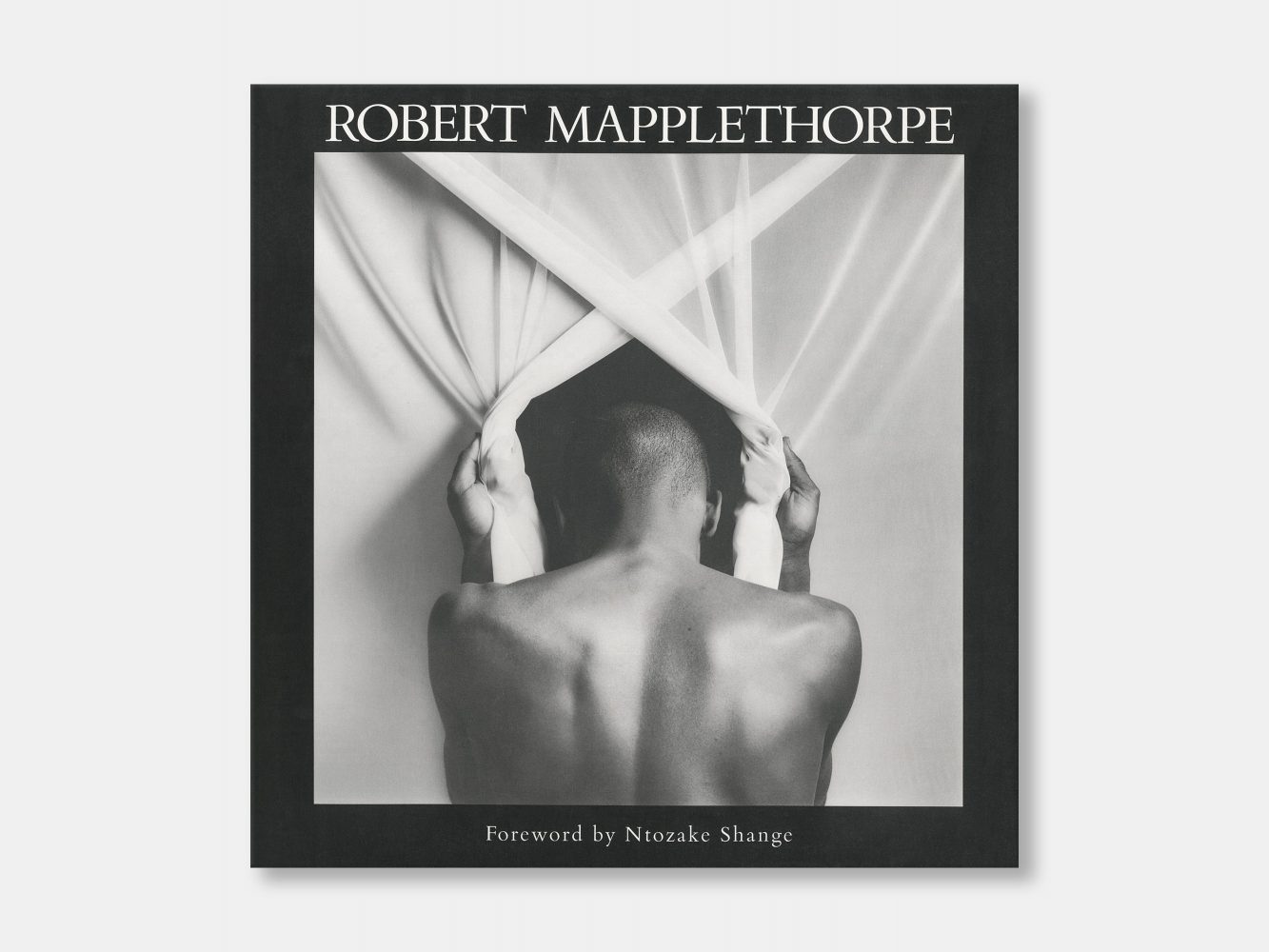

As curator Sylvia Wolf notes: ‘The highly stylised, neoclassically inspired works that Mapplethorpe made between the late 1970s and his death, in 1989, did not emerge fully formed.’2 While Mapplethorpe’s early Polaroids are rightly appreciated as works in their own right, this period was formative. The Polaroid camera allowed him to freely experiment with certain subjects, genres and compositional devices that would come to define much his mature work and, ultimately, establish him as one of the most significant photographers of his generation. As Arthur C. Danto writes in the monograph Robert Mapplethorpe (2020): ‘What gives a certain authority to Mapplethorpe’s art is that virtually everything he ever did was there at the beginning: the self-portraits, the shots of Patti Smith, the sad pornography, the flowers.’ While undoubtedly foundational for Mapplethorpe, the Polaroid photographs were not the work of an apprentice but a precocious artist with a mature aesthetic sensibility and an established set of interests. In this regard, Danto summarises: ‘He began as he ended.’3

Mapplethorpe’s fascination with highly sexualised imagery was apparent from an early age. In 1963, he was caught stealing a magazine of gay pornography from a newsstand in Times Square; in the naked self-portraits taken in the early 1970s, we find an artist trialling the exhibitionist poses that his sitters would later adopt. But Mapplethorpe’s attraction was not solely libidinal.4 Rather, he was interested in locating aesthetic perfection within explicit images and, in doing so, liberating said images from the societal conventions that first deemed them immoral. ‘The point is not […] to stoke a sexual revolt or a desecrating process,’ writes art historian Germano Celant of Mapplethorpe’s erotica, ‘it is a question of appropriating the infinitude and vitality of all these things, of looking at images with a renovated perspective that rejects the negativity of suppression’.5

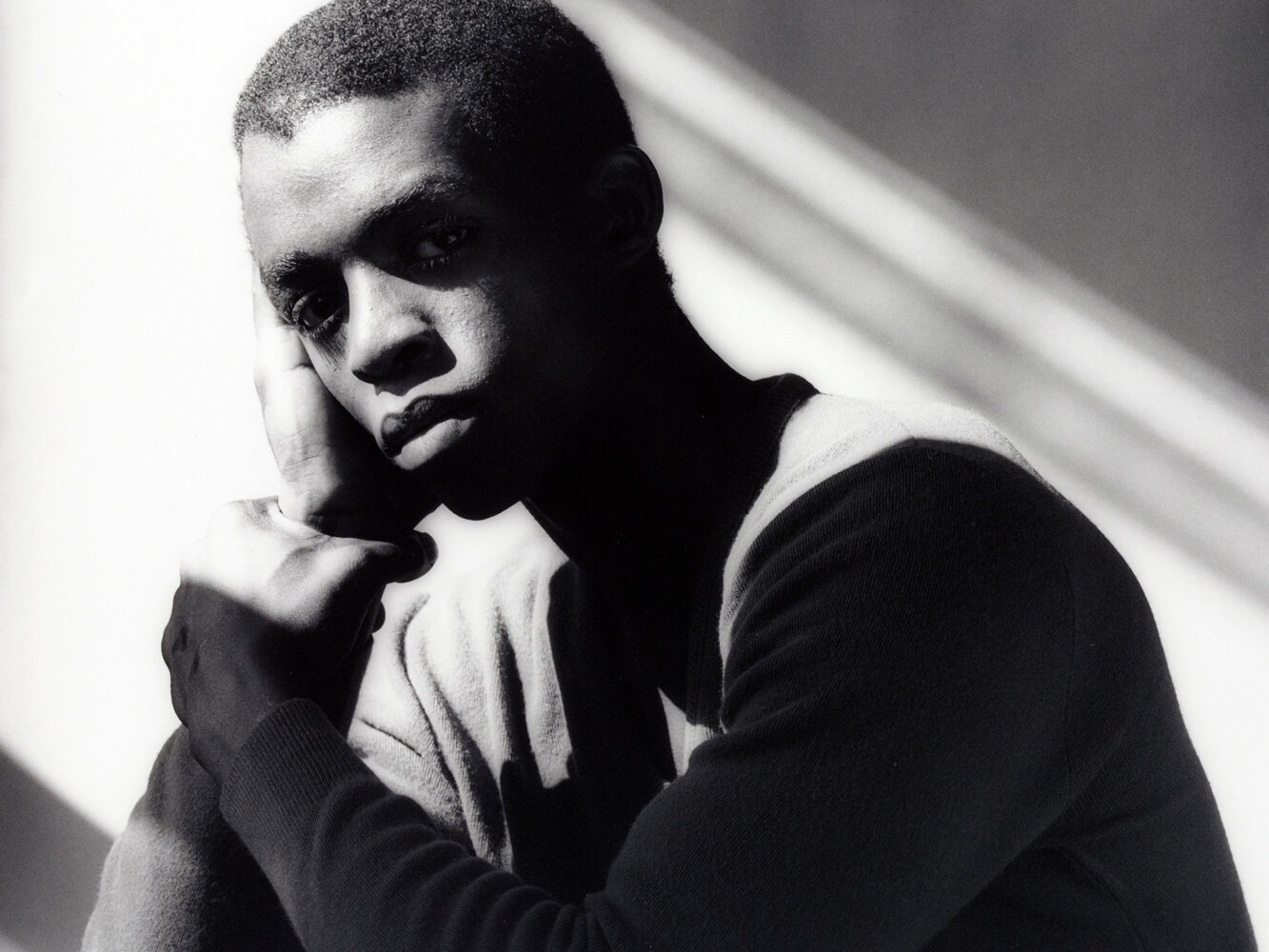

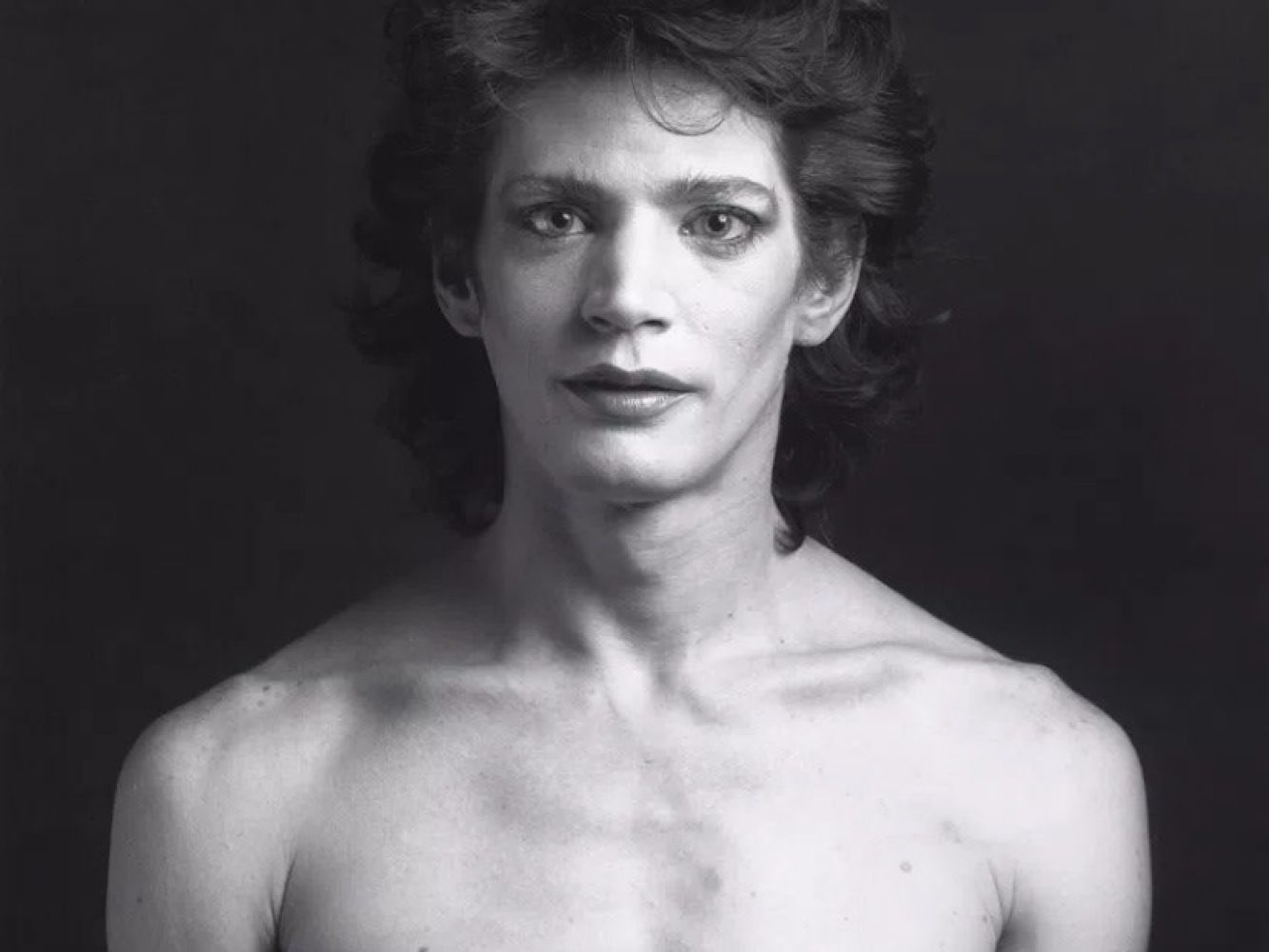

This ‘renovated perspective’ never intended to shock. ‘I don’t like that particular word, “shocking”’, Mapplethorpe once told the BBC, ‘I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before.’6 Indeed, the most ‘shocking’ element of Mapplethorpe’s erotic images is the sculptural quality of their composition: highly constructed, at times verging on the architectural. ‘Photography is just, like, the perfect way to make a sculpture’, Mapplethorpe told Anne Horton in 1987.7 In nudes such as Charles Bowman / Torso (1980), Raymond (1985) and Dan S. (1980), the latter of whom is bifurcated by a vertical shadow, we discern an artist who was as concerned with the natural flow of the naked body as he was with depictions of balance and harmony, structure and geometry. ‘This is the sphere of pure form,’ writes art historian Arkady Ippolitov, ‘geometrical balance of beauty and light, male and female, night and day, real and invented.’8

Mapplethorpe’s relentless pursuit of aesthetic equilibrium – what he termed ‘perfection in form’ – is evinced by his photographs of flowers, which he interacted with in much the same way that he did the naked form. ‘My approach to photographing a flower is not much different than photographing a cock’, he told Gerrit Henry in 1982. ‘It’s about lighting and composition. […] It’s the same vision.’9 Certainly, there is a compositional consistency to consider: Mapplethorpe’s treatment of light around stamen and petals is comparable to the way in which he overlays shadows on Lisa Lyon, Ken Moody or Patti Smith. In a series of lilies from the mid-1980s, one can discern human eroticism; the outstretched stems of Iris (1982) are structurally similar to the spread legs of Derrick Cross (1985). But Mapplethorpe’s egalitarian ‘vision’ goes beyond formal similarities alone. Both his flowers and portraits fall within the same tradition of the memento mori – they are at once reflections on the inevitability of death and celebrations of the abundant life that precedes it.

The influence of Mapplethorpe is widespread and enduring. Just as he photographed prominent figures from the worlds of art, music, fashion and film, so too have these individual sectors adopted and evolved his distinctive aesthetic. His work has been a reference point for writers including Michael Cunningham, Elif Batuman and, Hilton Als and designers such as Hedi Slimane, Ann Demeulemeester and Raf Simons. (‘The quality [of his work] is almost shocking’, Simons said of Mapplethorpe on the occasion of his 2017 collaboration with the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. ‘It’s like almost every photograph is mind-blowing.’10) His cover image for Patti Smith’s Horses, shot in 1975, remains iconic. Recent exhibitions of Mapplethorpe’s work at Alison Jacques Gallery have opened up further connections between creative industries, bestowing curatorial responsibilities upon the likes of David Hockney, Juergen Teller, Scissor Sisters and Patti Smith. The fact that Mapplethorpe’s legacy has been so widely distributed is, in a way, a testament to his enduring belief that beauty and form – perhaps even ‘perfection in form’ – can be found in any walk of life.

In its beauty and sculptural artistry, Mapplethorpe’s art endures as a rebuke to staunch conservatism and a testament to the internal and external beauty of people – of friends and celebrities; of those who push against the fixed conventions of their time. It could be said that Mapplethorpe’s ambition was to liberate his models (whether flowers, figures or still lifes) from the various repressions and assumptions of their contemporaneous circumstances and allow them to exist as visual things in their own right. ‘The recourse to the nude allows the photographer to strip the people Mapplethorpe loves […] of all external elements’, writes Celant, ‘freeing them of their social fetters in order to place them on a pedestal outside of time.’11

- Arena: Robert Mapplethorpe, 1988, dir. by Nigel Finch, BBC Films

- Sylvia Wolf, Polaroids: Mapplethorpe (New York: Prestel, 2008), p.20

- Arthur C Danto, Robert Mapplethorpe (London: Phaidon, 2020)

- Speaking of his early attachment to X-rated magazines, Mapplethorpe noted: ‘It’s not a directly sexual [feeling], it’s more potent than that.’ Wolf, p.20

- Germano Celant, ‘Mapplethorpe as Neoclassicist’, Robert Mapplethorpe and the Classical Tradition (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publishing, 2004), p.49

- Arena: Robert Mapplethorpe, 1988

- Anne Horton, ‘Robert Mapplethorpe: Interview January 11, 1987’, Robert Mapplethorpe 1986 (Berlin: Raab Galerie, 1987), p.12

- Arkady Ippolitov, ‘Images and Icons’, Robert Mapplethorpe and the Classical Tradition (Guggenheim Museum, New York; 2004), pp.21–22

- Gerrit Henry, ‘Robert Mapplethorpe—Collecting Quality: An Interview’, The Print Collector’s Newsletter, 1982

- Rebecca Voight, ‘At Pitti Uomo, Raf Simons Transforms Robert Mapplethorpe’s Photography Into Fashion’, W Magazine, June 2016

- Celant, p.49

Works

Press

Robert Mapplethorpe: Subject Object Image review – penises, perfection and Patti Smith

30 November 2023

A Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective, Ottessa Moshfegh’s Eileen and oysters topped with Monster Munch

15 December 2023

Exhibitions

Books

News

Robert Mapplethorpe

‘ARTIST ROOMS LOUISE BOURGEOIS | HELEN CHADWICK | ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE’, NATIONAL GALLERIES OF SCOTLAND, EDINBURGH

Robert Mapplethorpe

in ‘Fragile Beauty: Photographs from the Sir Elton John and David Furnish Collection’ at Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Robert Mapplethorpe

in ‘Fragile Beauty: Photographs from the Sir Elton John and David Furnish Collection’, The Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Robert Mapplethorpe

in ‘Filippo de Pisis and Robert Mapplethorpe: A Distant Conversation’, Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Gordon Parks and Robert Mapplethorpe

in ‘ICP at 50: From the Collection, 1845–2019’, International Center of Photography (ICP), New York

Robert Mapplethorpe & Ana Mendieta

in ‘Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography’, Barbican, London